Five Essential Thinkers Who Shaped Modern Systemic Work

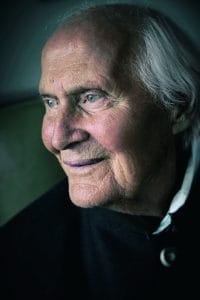

Bert Hellinger - the founding father

No conversation about systemic work can begin without acknowledging Bert Hellinger (1925-2019), the German psychotherapist who developed "Family Constellations" in the late 20th century. This groundbreaking approach revealed how family members often unconsciously carry burdens and maintain patterns that serve the larger family system rather than their individual well-being.

What makes Hellinger's work so revolutionary is how he demonstrated that these systemic patterns can span generations, with events from decades past continuing to shape current behaviors. His core insight—that problems which appear individual often serve a function in the larger system—fundamentally changed how we understand human dynamics.

If you're new to systemic work, starting with Hellinger gives you the foundational understanding that everything belongs to something larger, and that meaningful change requires engaging with this larger field of connections.

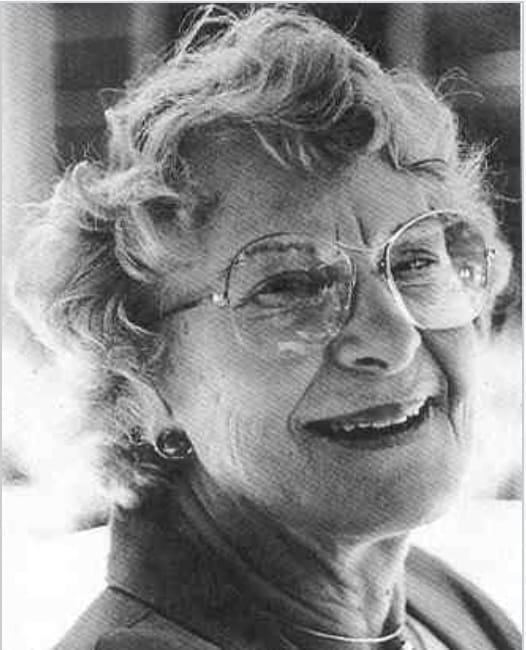

Virginia Satir - the communication pioneer

While Virginia Satir (1916-1988) predates the formal development of what we now call systemic work, her contributions to family therapy and organizational dynamics make her essential reading for anyone exploring this field.

Satir's genius lay in recognizing communication patterns as the visible manifestation of invisible systemic dynamics. Her famous "Satir Categories" identified predictable roles people adopt under stress (placating, blaming, computing, distracting, and later, congruence) that maintain system balance, even when dysfunctional.

What I love about Satir's approach is its profound humanity—she understood that behind every problematic pattern is a yearning for connection and belonging. Her work helps us see that even the most frustrating behaviors in a system often represent creative adaptations to maintain some kind of order.

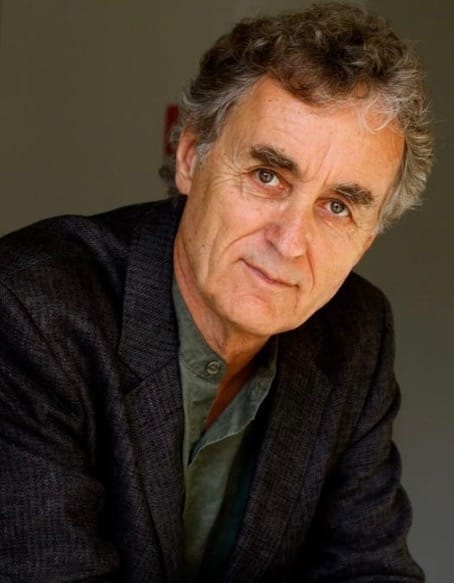

Peter Senge - the learning organization architeact

For those specifically interested in applying systemic thinking to organizations, Peter Senge's work provides essential frameworks and practical applications. His 1990 book "The Fifth Discipline" introduced the concept of the learning organization and brought systems thinking into mainstream business consciousness.

Senge demonstrates how organizations function as complex systems where interventions often create unintended consequences due to feedback loops and delays. His work helps us understand why well-intentioned changes frequently fail when they don't account for the full systemic context.

What makes Senge particularly valuable is his ability to translate abstract systemic concepts into practical tools like "systems archetypes"—recurring patterns that appear across different organizations and contexts. These archetypes help us recognize and work with common systemic challenges before they become entrenched problems.

Donella Meadows - the systems scientist

While many practitioners focus on the applied interpersonal aspects of systemic work, Donella Meadows (1941-2001) provides the scientific foundation. Her work on system dynamics, particularly her concept of "leverage points," offers invaluable insights for anyone looking to create effective change within complex systems.

Meadows identified twelve places to intervene in a system, arranged in order of increasing effectiveness. What's fascinating about her findings is that the most common intervention points (like changing parameters or adding buffers) are typically the least effective, while the most powerful leverage points involve changing the system's paradigm or mindset.

Her accessible writing style makes complex concepts understandable without oversimplification. If you want to understand why some systemic interventions create profound change while others barely make a ripple, Meadows offers the clearest explanation I've encountered.

Frotjof Capra - the systems philosopher

For those drawn to the philosophical dimensions of systemic work, Fritjof Capra provides a rich intellectual foundation. His book "The Web of Life" explores how systems thinking represents a fundamental shift in how we perceive and interact with the world.

Capra's contribution lies in connecting systemic approaches across disciplines—from biology and ecology to social organizations and cultures. He helps us understand that systemic work isn't just a methodology but part of a larger paradigm shift from mechanistic to holistic thinking.

What I find most valuable about Capra's perspective is how he illuminates the natural intelligence of systems. He shows that many of the patterns we observe in human systems reflect broader patterns in living systems throughout nature, helping us work with rather than against these natural dynamics.

Beyond the Big Five: the next generation

These five names provide an excellent foundation, but systemic work continues to evolve with contributions from practitioners around the world. Once you've explored these foundational thinkers, you might want to discover contemporary voices applying systemic principles to specific contexts:

For organizational applications, look to Gunthard Weber and Jan Jacob Stam

For coaching applications, explore Cecilio Fernández Regojo and John Whittington

For educational applications, consider Marianne Franke-Gricksch's work

For practical implementation in organizations, explore my work, particularly my accessible frameworks and "Moving Questions" that help teams immediately apply systemic principles to everyday challenges

Remember, systemic work isn't just something to read about—it's something to experience. The real learning comes through practice, observation, and developing your own "systemic eyes" to perceive the invisible connections that shape our lives.

As you begin your exploration of systemic work, you'll encounter a group of pioneering thinkers who have shaped this powerful approach to understanding the invisible connections that influence our lives and organizations. Whether you're just becoming curious or are ready to apply systemic principles to your team, family, or organization, these five influential thinkers are the perfect starting point for your journey.